The Aztecs and Cocoa

The Mexica are the specific group that founded Tenochtitlán, the core of the Aztec Empire. On the other hand, “Aztec” refers to the civilization that developed from this city-state, including several peoples under its rule.

The use of cocoa spread among the Mexica around the year 1400 AD. C, who came into contact with the ancient Mayan cities between the 12th and 15th centuries, and from that moment on they adopted the cocoa drink.

Shortly after, new chocolate regions were developed on the Pacific coasts, such as the province of Nicoya in the current territory of Costa Rica to the lowlands of Colima, in Mexico.

For the Aztecs, cocoa was a luxury product, whose regular consumption was reserved for the elites. “Techocolat” was a bitter and concentrated concoction prepared from cocoa, reserved for the emperor, nobles and warriors.

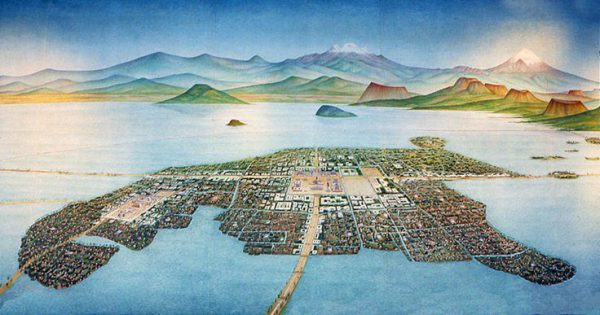

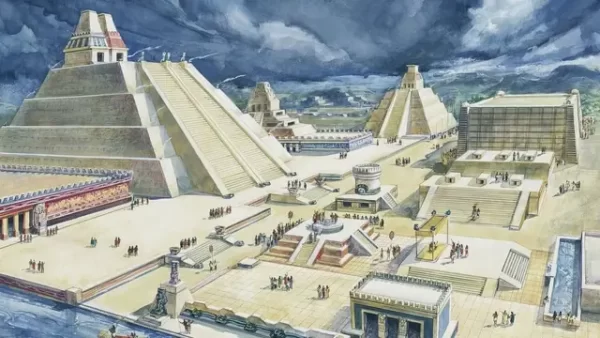

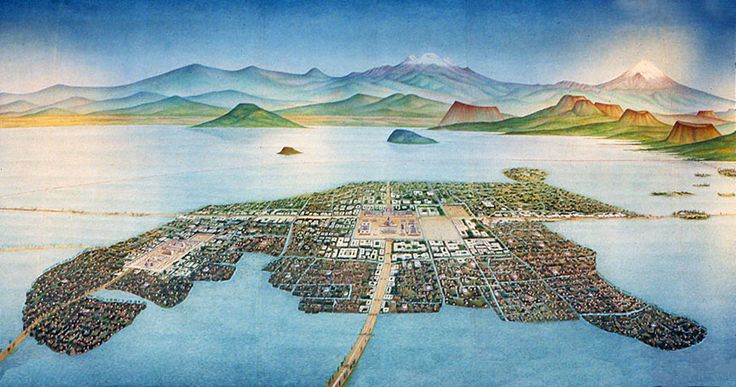

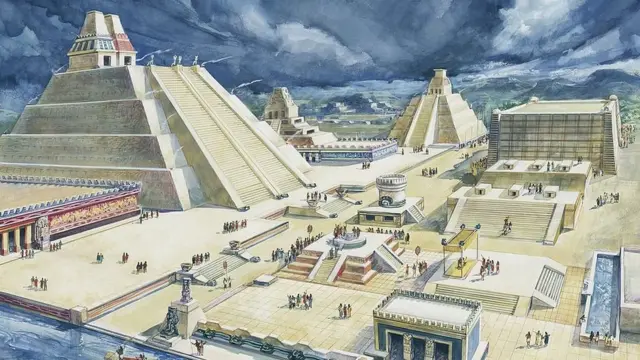

Recreation of Tenochtitlán

A passage from the Xolotl Codex relates that Aztec soldiers, when they went on campaign, carried with them roasted corn, peppers, ground beans, and ground cocoa.

Bernal Díaz del Castillo points out the presence of cocoa in the Tlatelolco market (the most important in Mexico-Tenochtitlán), and that its use at specific times was widespread in the population.

To prepare the cocoa drink, the Aztecs first roasted the beans and ground them into powder, sometimes along with other seeds.

The powder was put in a glass to which water was then added, beaten and transferred to another container to receive the foam. Then ingredients such as vanilla or aromatic plants and flowers were added to obtain drinks of different colors and aromas (red, orange or whitish).

The Aztecs mixed chili with roasted and ground cocoa beans, and added corn flour as an emulsifier.In addition, they invented the grinder, with which they increased the appearance of foam.

Recreation of Tenochtitlán

The Mexica had the custom of drinking cold chocolate, unlike the Mayans of Yucatan. Merchants, both before leaving and upon returning from their long journeys to distant lands, held rituals dedicated to the gods of commerce and cocoa in which they drank cocoa, celebrated with banquets, and smoked Mapacho.

As merchants improved their social position, rituals became more and more complex, sacrificing slaves and consuming psychoactive mushrooms.

The warriors were always provided with their rations, which included ground cocoa in the form of balls, roasted corn, crushed beans, and bunches of dried chili peppers. At the ceremony where a new eagle knight or tiger knight was invested, it was also customary to drink cocoa.

The chocolate reserved for dignitaries was called “tlaquetzalli”, which means “valuable thing”.During the Postclassic period (1000 to 1550 AD), cocoa acquired the quality of currency and the Mexica empire established it as tribute.

The Mexica used to grind the grains dry with corn, obtaining a powder called cacahuapinolli. However, the most important gastronomic use of cocoa was the preparation of a refreshing, stimulating, somewhat bitter cold drink that was obtained by grinding the beans and dissolving them in water, which Spanish chroniclers describe as “a very tasty foam.”

Fray Bernardino de Sahagún

Fray Bernardino de Sahagún was a Franciscan missionary, author of several works in Nahuatl and Spanish. His General History of the Things of New Spain, composed of twelve books, is his main work.

In these writings he recounts the cocoa production process that the Mexica followed:

“Grind it first this way: the first time grind or crush the almonds; the second time a little more ground; and the third and very last time, very ground, they were mixed with very cooked and washed corn grains, and once cooked and mixed, they poured water into a glass; and if they add little, they make nice cocoa; and if there is a lot, it does not foam, since to do it well the following is done and kept: it is convenient to know, that it is strained, then (…) it is raised so that it drips and with this the foam is raised, and it is poured apart, and sometimes it thickens too much and mixes with water after grinding, and those who know how to make it well made and beautiful, and such that only gentlemen drink it, white, sparkling, russet, red and pure, without much mass.

According to Brother Bernardino de Sahagún, who is considered the greatest expert on the Nahuatl language among the conquerors of the time and whose writings have been classified as “ethnographic monuments” among the Tenochca Mexica, only the nobles and those who had distinguished themselves in During the war they had the right to consume cocoa drinks without any permission; Most of the population could only drink it in certain ceremonies and “if they drank it without a license, it would even cost them their lives.” Among the Mexica it became known as yollotlieztli, “price of blood and heart.”

Starting from the basic recipe, other ingredients were added to obtain different results; Sometimes it was drunk without adding corn, or herbs, fruits and flowers were added. Honey was used to sweeten it. Hot chocolate was rare and considered a great delicacy.

Bernal Díaz del Castillo (2005) describes the customs of Ahuitzotl’s nephew and Axayacatl’s son, Moctezuma:

“They brought in cups of fine gold with a certain drink made from the same cocoa; They said it was to have access to women and then we didn’t look into it; But what I saw was that they brought about fifty large jugs made of good cocoa, with its foam, and he drank from that, and the women served him while drinking with great respect.”

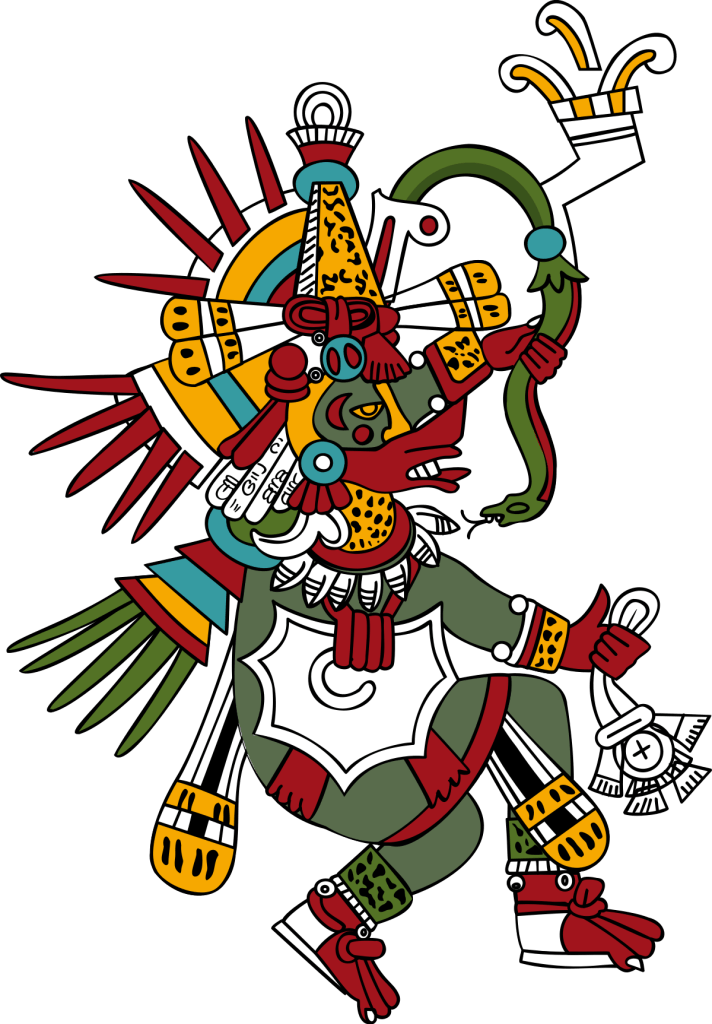

Quetzalcoatl

Cocoa Legend

The Mexicas, who absorbed the culture of the Toltecs, adapted the same legend that they had about cocoa, also shared by the Mayans: The god Quetzalcóatl, represented as a feathered serpent, came down from the heavens to transmit wisdom to men and He brought a gift: the cocoa plant.

The other gods did not forgive him for making known the divine food and took revenge by banishing him: he was expelled from their lands by the god Txktlpohk, just as in Greek mythology fire was stolen from the gods by Prometheus (The Mayans and Aztecs related cocoa with fire and water).

According to Aztec legend, when the god Quetzalcoatl came down to earth to give humanity agriculture, science and the arts, he married the beautiful princess of Tula.

To celebrate, he created a paradise where cotton was born in different colors, the water flowed crystal clear and there were all kinds of precious stones, plants and trees, among which the cacahuaquahitl, the cocoa tree, stood out.

But this was the food of the gods, who wanted to take revenge on Quetzalcoatl for having handed him over to men, and they murdered his wife. Desolate, the god cried over the bloody earth and there sprouted a tree with the best cocoa in the world, whose fruit was bitter like suffering, strong like virtue and red like the princess’s blood.

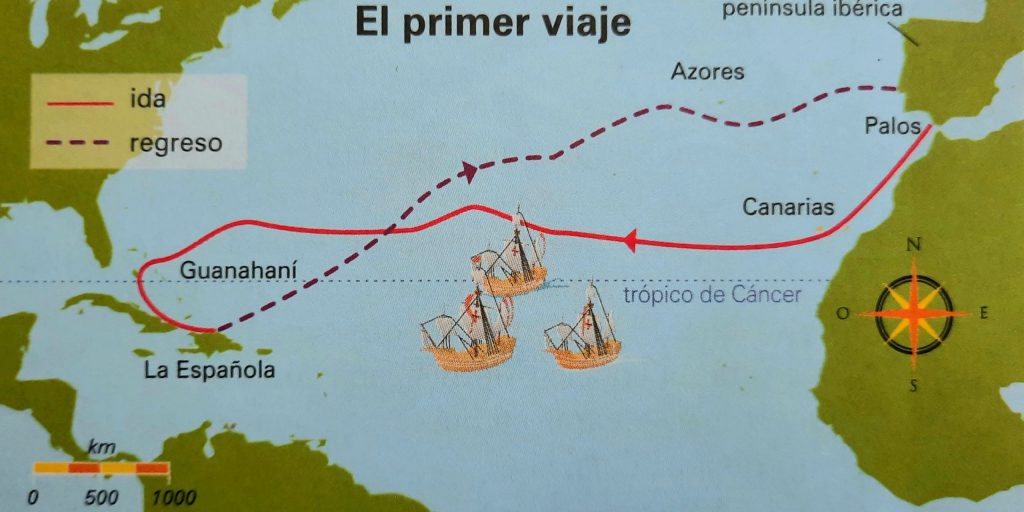

Cristobal Colón

Cristobal Colón was the first among Europeans to discover cocoa. On his fourth and final voyage to America in 1502, while near the island of Guanaja, off the coast of Honduras, his ship was boarded by a Mayan vessel loaded with goods in exchange.

Columbus did not know how to evaluate the real value of the cocoa seeds that the indigenous people offered him, nor did he have the opportunity to discover how they were worked to prepare a drink with them, which he never tried, but he did observe the high consideration of the that were objects and took some to the court of Castile.

As the chronicles of the Conquest attest, for the first Spaniards who landed in the New World, cocoa was simply a curiosity and, at least initially, it was not its nutritional use that attracted them, but the monetary value of the beans.

Cristobal Colón’s son, Hernando, relates: “And many almonds that they use as currency in New Spain, which seemed to be highly valued, because when the things they were bringing were placed on the ship, I noticed that some of these almonds fell , everyone tried to catch them as if an eye had fallen out” History of the admiral, Hernando Colón. (Colón 275).

Moctezuma and Hernán Cortés

Montezuma II

Moctezuma, governor of Mexico-Tenochtitlán during the conquest of Mexico by the Spanish, distinguished himself as an excellent warrior and led the campaigns undertaken by his uncle Ahuitzotl, who expanded the Aztec Empire to the very lands of Guatemala, a region coveted for its cocoa production.

Under his rule, the city of Tenochtitlan managed to maintain its power and the dominance it exercised over other towns.

The Aztec emperor implemented a series of measures that earned him the reputation of an extravagant king: No one could look him in the eye and they had to talk to him without looking up. He couldn’t touch him or turn his back on him.

According to legend, Emperor Montezuma drank fifty cups of cocoa a day.

This foamy drink was also used in religious ceremonies by Xochiquetzal, the goddess of fertility. His economic system contemplated the price to pay using cocoa beans as currency: with one hundred you would get a slave, and with twelve, the services of a courtesan.

Since before the reign of Motecuhzoma II, the Aztec nobility and its merchants (pocbeta) held lavish ceremonies and large banquets where they drank cocoa.

They were especially interested in the species cacao lizard (T. pentagonum), which they associated with Cipactli (crocodile in Nahuatl).

According to Montezuma II, the cocoa drink could sustain a man without eating for an entire day.

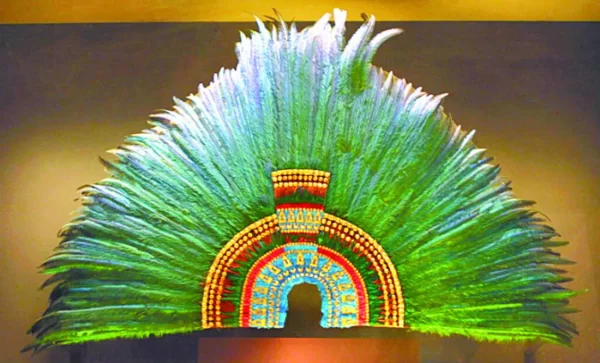

Montezuma’s Plume

The “Peñacho de Montezuma” is a headdress of quetzal feathers set in gold that is thought to have belonged to Montezuma.

It is made with quetzal feathers mounted on a gold base adorned with precious stones. It has 1,544 gold metal pieces, the blue feathers are from the xiuh totol bird, and the gold pieces are shaped like half-moons with precious stones.

It has a height of 116 cm and a diameter of 175 cm. It has a pink area of tlauquechol feathers and another area of brown cuckoo feathers, from which comes a row of green quetzal feathers, some up to 55 cm long, followed by another area also of quetzal feathers; In total it has more than 222 quetzal feathers.

The plume was brought to Europe by Hernán Cortés; It could have been a gift from Moctezuma Xocoyotzin after the arrival of the Spanish conquering explorer to the Mexican coasts.

Cortés gave the plume to King Charles I of Spain and V of Germany, from the House of Habsburg. Years later, it was recorded in the inventory of assets of Archduke Ferdinand II of Habsburg, a relative of Charles I, after his death in 1595.

Between 1799 and 1802, it was moved to Ambras Castle to protect them during the Napoleonic Wars. It was taken to Vienna in 1806, and 72 years later it became property of the Austrian State. In recent years, the Mexican State has initiated different campaigns to try, still without success, for this historical piece to be returned to its territory.

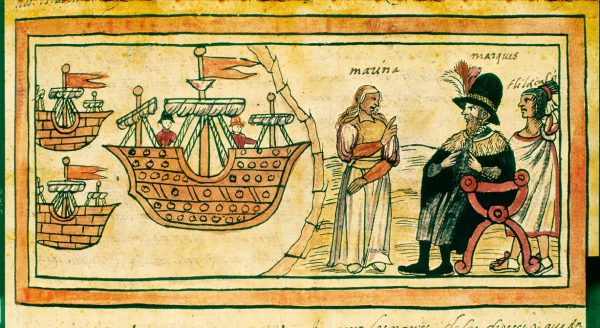

Moctezuma and Hernán Cortés

Hernan Cortes

It was through the work of Hernán Cortés, who arrived in Mexico in 1519, that the Spanish began to become interested in cocoa.

In April 1519, Spanish troops led by Hernan Cortés landed in a town in the Gulf of Mexico, in the current State of Veracruz, which at that time was territory of the Aztec Empire, governed by Moctezuma.

Upon disembarking, Cortés was mistaken for the reincarnation of the god Quetzalcoatl and welcomed with honors by the emperor Moctezuma II because, according to legend, Quetzacoatl, the bearded and white-skinned god, had promised his return precisely in the year Ceacatl, 1519. (Monreal and Tejada).

The Spanish conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo recounts, in his “True History of the Conquest of New Spain,” the welcoming banquet that Emperor Moctezuma offered to Cortés:

“From time to time they brought in cups of fine gold with a certain drink made with

cocoa, which they said was to have access to women; and then we didn’t look into it; more what I saw, that they brought about fifty jugs made of good cocoa with its foam, and from that he drank and the women served him while drinking with great respect (…) Because Moctezuma was fond of pleasures and songs (… ) And when he finished eating they also put three very painted and gilded pipes on him, and inside they had liquidambar mixed with a herb called tobacco, and after they had danced and sung to him and set the table up, he would take the smoke from one of those pipes .”

The Anonymous Conqueror, Mexico, Editorial América:

“The tree that produces this fruit is the most delicate of all, and is only born in strong and warm lands; before planting it they plant two other very tall trees, and once these are already about the height of two men, they plant between the two this one that produces the said fruit, so that those others, because it is so delicate, guard it and defend it from the wind and the sun, and have it covered.

“And the saying Quetzalcoatl had all the riches of the world, gold, silver, green stones called chalchihuites and other precious things, and a great abundance of cocoa trees…” (Chimalpopoca Codex)

Cortés very soon understood the high nutritional value of cocoa, and began to distribute it to his soldiers: “[…] it is a fruit like almonds, which they sell ground, and they have it for so long that it is traded in currency throughout the land. and with it all the necessary things are bought in the markets and other places” “[…] a single cup of this drink strengthens the soldier so much that he can walk all day without needing to take other food” (Cortés 146).

Seeing that cocoa beans were used as currency and that the Aztecs attributed restorative and aphrodisiac virtues to the cocoa drink, Hernán Cortés created plantations in Mexico, Trinidad and Haiti, and even on an island in West Africa. From that island, cocoa cultivation spread to Ghana in 1879.

Teotihuacan

Teotihuacan

The Teotihuacan Archaeological Zone is located in the current state of Mexico, northeast of the Mexican capital. Teotihuacan means the “place where the gods were created” in Nahuatl and owes its name to the Mexica, who called it that when they found this great archaeological complex in ruins, six centuries after its abandonment, which belonged to a previous civilization.

Possibly, it was the Toltec civilization that built the Teotihuacan complex. It reached 22 square kilometers in area and was one of the cultural centers of the area, with the largest pyramids in Mesoamerica.

Teotihuacán was located in an area where the climatic conditions required for the cultivation of cocoa did not exist, and it was imported from the producing regions, in the area of the current Yucatan peninsula and in the jungles of Chiapas. There were close commercial relations between the Teotihuacans and the Mayans, who were in charge of its cultivation and sale.

Cocoa became one of the products associated with wealth, along with jade, precious feathers and jaguar skins. Its seeds were also used as currency.