Cocoa and the Mayans

The Chontal or Putun Mayan commercial networks, settled in the coastal plain of Tabasco and Campeche, expanded the commercial and symbolic value of cocoa throughout Mesoamerica during the final part of the Classic period (800-1000 AD).

The Mayans combined cocoa with young cocoa pods (tsih’té kakaw), adding honey (k’ab kakaw), or took it bitter without sweetening (ch’ah kakaw). Sometimes they combined it with pinole and achiote (axiotl), as a condiment and coloring to enhance its color and flavor. Other times, chili and vanilla (tlilxochitl) were added.

On other occasions they took it slightly fermented, with honey. Pochote seeds and leaves of a flower from Chiapas, called orejuelo, with a pepper-like flavor, were also added.

To increase its foam and give it body, the cocoa flower (cacaoaxóchitl) was incorporated. Other ways to take it was by adding corn, pulque and heart flower (Yoloxochitl).

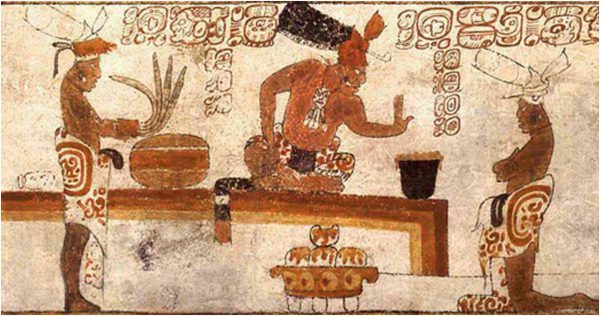

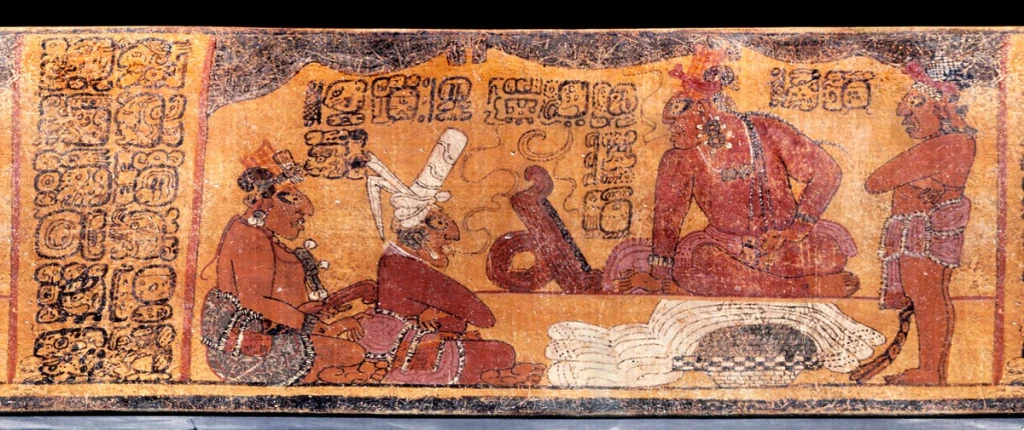

The utensils used to consume cocoa drinks had a ritual character and were carefully crafted and decorated. They could be made of precious materials, such as stone, ceramics or carved wood.

Francisco Hernandez

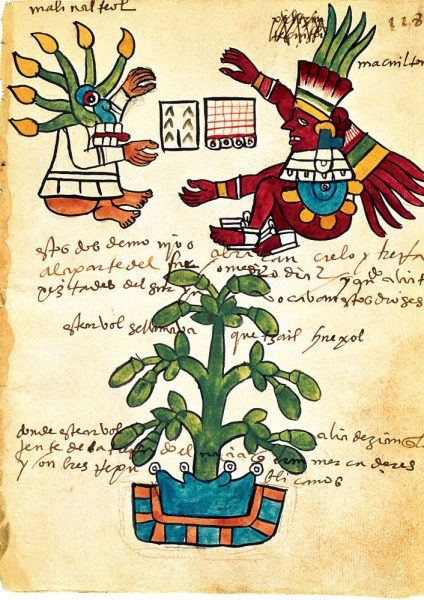

Francisco Hernández, Castilian doctor, botanist and ornithologist chosen by Felipe II to lead an expedition to New Spain (present-day Mexico), described various cocoa-based drinks, such as atextli, which was prepared with cocoa and corn.

He relates that the fruit of mecaxóchitl, xochinacaztli and vanilla or tlixóchitl were added. “the property of these compound drinks is to excite the venereal appetite; The simple refreshes and nourishes greatly. Another type of drink is made with twenty-five cacahoapatachtli beans, as many cocoa beans and a handful of Indian grain (corn). None of the things mentioned above are usually added, which are hot, since only refreshment and refreshment are sought in this drink. nutrition”.

The third drink that Francisco Hernández mentions is chocolate (chocólatl), prepared with cacáhoatl and pochotl (pochote) grains, in equal parts, and a handful of corn.

Cacáua atl: Corn drink with cocoa water.

Chilcacáuatl: Mixture of cocoa with chili.

Atlanelollo cacáuatl: Natural cocoa drink, without other ingredients.

Xochayo cacáuat: Mixture of cocoa with dried and ground flowers.

The Mayans made the drink even foamier by pouring it from an elevated container to another on the ground; Later, the Aztecs invented a utensil called a grinder to cause foam to appear.

In the Mayan area it was used to heal sores and wounds through the application of enemas or as a psychotropic. The Itza introduced its use as currency.

Since the end of the Preclassic period, the Mayans prepared chocolate, containing some fermented mucilage from the same almond, to which they added some kinds of highland mushrooms, such as Psylocibe cubensis or Psylocibe semilanceata, called by the Mayans as “flesh of the gods.” ”.

The Mayan shamans or priests thus came into contact with supernatural beings, humans or animals. (Kerr, vase photo collection K8763).

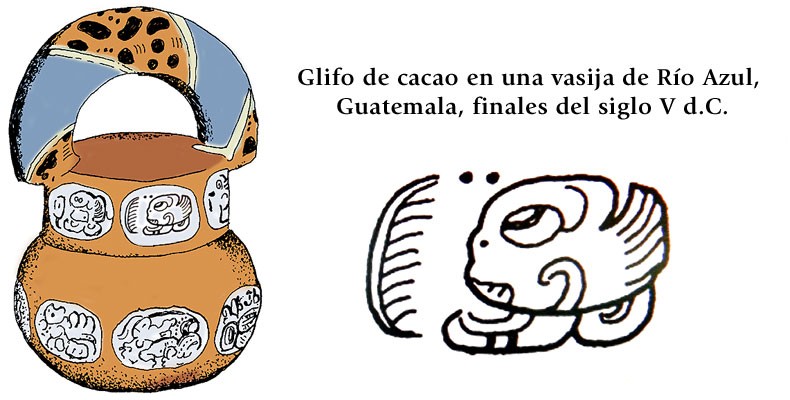

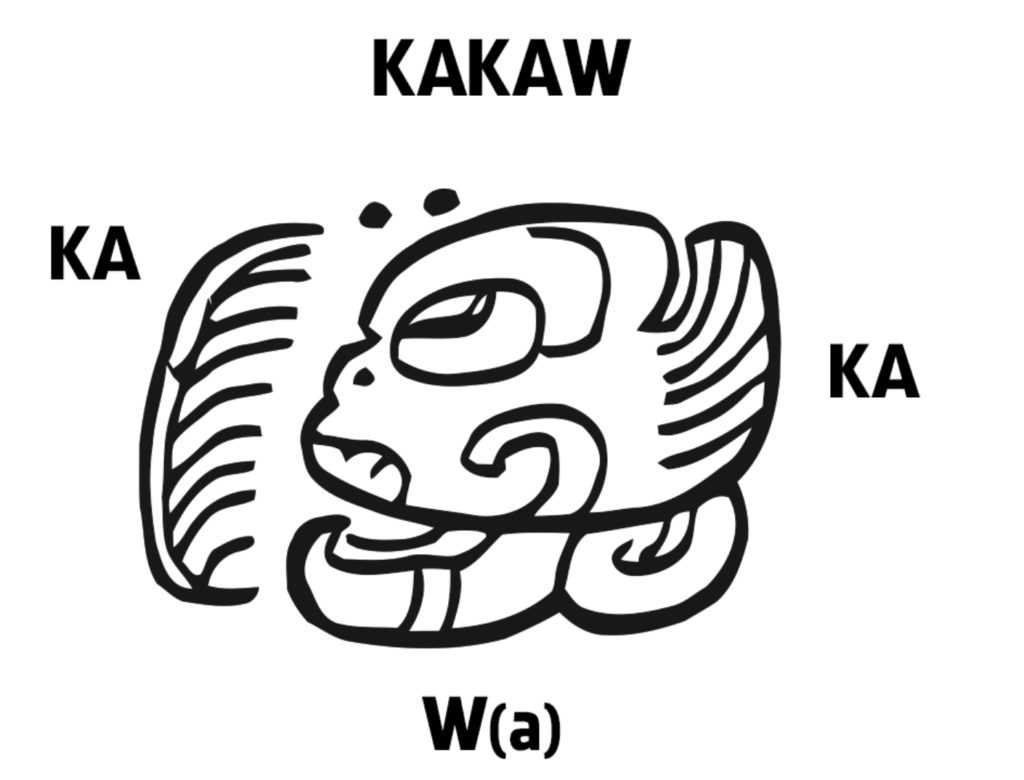

Kakaw Word: Archaeological Records

The word kakaw existed among the Mayans since the beginning of the classic period, around 400 AD. The glyphs of the Mayan inscriptions are the only evidence of the existence of the word kakaw before the arrival of the Spanish.

Mayan writing is logo-syllabic; The word kakaw is written by repeating the syllable ka and the suffix wa, obtaining ka-ka-wa, and by removing the vowel from the last syllable, the word kakaw is obtained.

The syllable ka derives from the word kay (fish). The glyph that represents this syllable is that of a fish, full body, just its head, or a comb-shaped sign, which represents its fin.

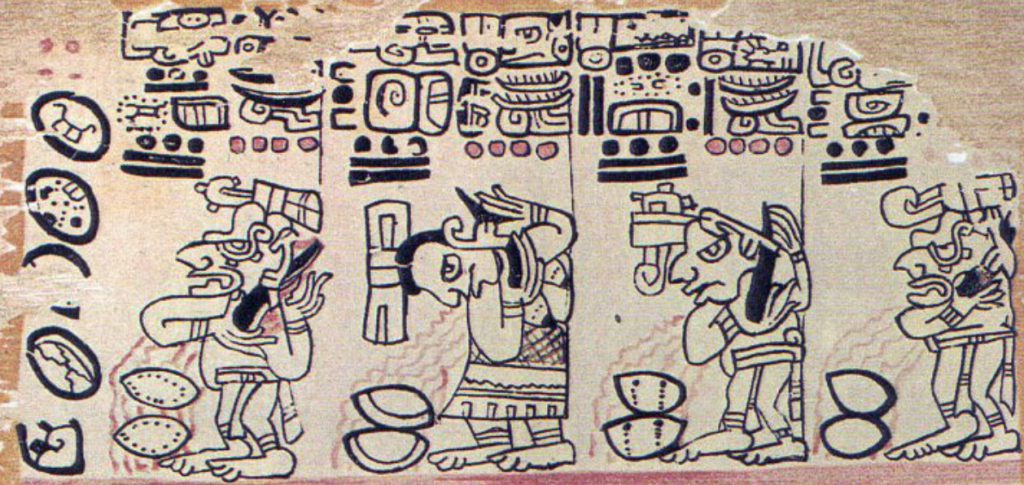

Sometimes only one syllable “ka” is noted in the shape of a fish, and one or two dots in front of its head, indicating that the syllable is doubled. This writing system appears in the Dresden and Madrid Mayan codices.

As for the third and last sign of the glyph, with the syllabic value wa, it is a sign of corn, which was derived from the word waaj (tortilla, tamale).

Popol Vuh Book

Origin and authorship of the Popol Vuh

The Popol Vuh is a small book that tells the origin of the Mayan peoples, their migrations and development after the collapse of their Empire. It was written at the time of the conquest, between 1554 and 1558 by Brother Francisco Ximénez, an evangelized Mayan. This book is probably the translation of an ancient Mayan book in which the author translates the entire context of the Mayan worldview into an evangelical and Christianized language.

It cannot be assured that this was the Mayan worldview before the arrival of the Spanish ecclesiastics. Some historians, such as René Acuña, question the foundation of the book by pointing out that it is “designed and executed with Western concepts.”

Hidden for a century and a half, the Popol Vuh was discovered between 1701 and 1703 by Father Fray Francisco Ximénez, who translated it into Spanish. Carl Scherzer met it during his stay in Guatemala and published it in 1857.

Popol Vuh and Cocoa

According to the Popol Vuh, cacao was considered one of the four cosmic trees, and had an essential association with the sacred plant par excellence of Mesoamerica: corn. It also had a meaning strongly linked to blood and sacrifice.

In the Popol Vuh it is told how the gods look for food for humans, whom they have just created:

“And in this way they were filled with joy, because they had discovered a beautiful land full of delights, abundant in yellow ears and white ears and also abundant in pataxte (Theobroma bicolor) and cocoa… There was food of all kinds.”

It also tells the story of the twins Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué, two heroes who undergo metamorphosis into different forms of life. The twins are deceived and sentenced to death by the lords of Xibalbá (underworld), but they manage to resurrect in the form of fish. Upon regaining their human form, Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué kill the gods of Xibalbá.

The fish associated with cocoa is the catfish, which commonly appears adorning ceremonial vessels found in Mayan royal tombs.

Another story from the Popol Vuh explains that Xmucané, mother of Hunahpú and grandmother of the twins Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué, is the creator of cocoa-based drinks.

Dresden Codex

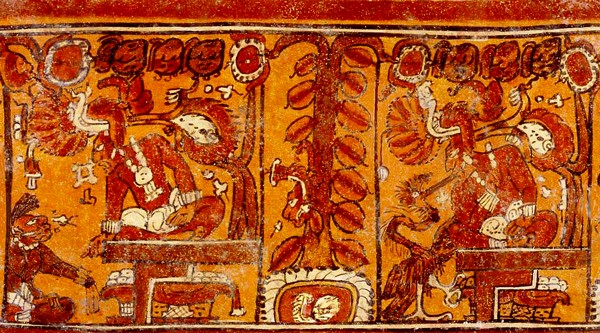

The Dresden Codex dates from the Classic Mayan period, (From 250 AD). It recounts the ritual activities linked to its 260-day sacred calendar (the gestation of a human being), and seated deities are depicted holding cocoa fruits or plates overflowing with cocoa beans. The text, written above each god, confirms that what he has in his hand is his cocoa.

According to the historian Erick Velásquez, the Dresden codex is a set of divinatory almanacs, astronomical, calendrical and numerical tables, which are intended to predict the future, and provide valuable information about the myths and attributes of the gods.

Madrid Codex

In a representation from the Madrid codex, a young god crouches down while he picks branches from a cocoa tree; A quetzal that flies over it carries a cocoa fruit in its beak. In the associated text, the word KAKAW appears.

Elsewhere in this codex, four gods pierce their ears with obsidian lancets, letting rains of blood fall on cocoa fruits. The hieroglyphic text mentions specific offerings of incense and cocoa beans, and many gods are depicted eating or holding cocoa beans.

Cocoa and Mushrooms: Mayan Tradition

There is numerous archaeological evidence about the use of mushrooms by the Mayans.

The mushroom stones stand out, statuettes that date from the preclassic period of the history of Ancient Mexico. Most have been found in Guatemala, and also in El Salvador, Honduras and Mexico; and even in areas that do not have a Mayan population, such as Veracruz and Oaxaca.

Ceramics have also been found used by rulers and lords to drink chocolate, sometimes mixed with mushrooms, seeds and psychoactive flowers; In the Dresden codex there appears the image of a person or god holding a mushroom from which other mushrooms emerge.

Fray Tomás de Coto was a Guatemalan Franciscan who wrote the Vocabulary of the Cakchiquel or Guatemalan language in the mid-17th century, and differentiates two types of mushrooms: that of the underworld and that of lightning:

“…it is necessary to know them to eat them, because there are some that are evil and deadly, and, at least those who eat them, make them lose their minds. They call these kaizalah ocox or xibalbay ocox (underworld mushroom).” While the Quiché term Kakuljá ocox refers to the “lightning fungus”, which would reflect the relationship of fungi with rain.

In both cases the references correspond to the Mayan highlands, where the Amanita muscaria grow. Cacaco produces a slight MAOI effect, responsible for part of the synergy between cocoa and magic truffles. Cocoa should never be mixed with another MAOI.

Ek Chuah, god of cocoa

Ek Chuah is the protective god of cocoa in Mayan mythology, also known as “Black God” or “God of Commerce”. He was both the god of cocoa and that of merchants and travelers.

Cocoa was a fundamental commodity on Mesoamerican trade routes, and was used as currency to exchange all types of goods and services.

Ek Chuah had its own day in the Mayan calendar, April 25, the day on which they were offered sacrifices and cocoa. In Mayan art, Ek Chuah is depicted as a robust warrior, adorned with the attributes of trade and war; a merchant’s bag hanging over his back, and a spear or shield.

Ek Chuah is a patron deity of travelers and travel.Cocoa was one of the most valuable products of Mayan traders and was sometimes used as currency. As Ek Chuah was the patron saint of cocoa, cocoa owners held special ceremonies and festivals in his honor. One of them was celebrated during Muwan, a “month” in the Mayan solar calendar or haab.

Ek Chuah sometimes appeared in combat, usually with Buluk Chabtan, the god of war, violence and sacrifice. This interaction has been interpreted as the need of traveling merchants to be able to protect themselves from hostile attacks. In the Madrid codex, they are closely linked and sometimes almost indistinguishable from each other.

Ixcacao

Ixcacao, whose name is intrinsically linked to cocoa, was a Mayan goddess of fertility and abundance, a caregiver who offered physical and spiritual sustenance. In some legends, she was also a goddess of war.

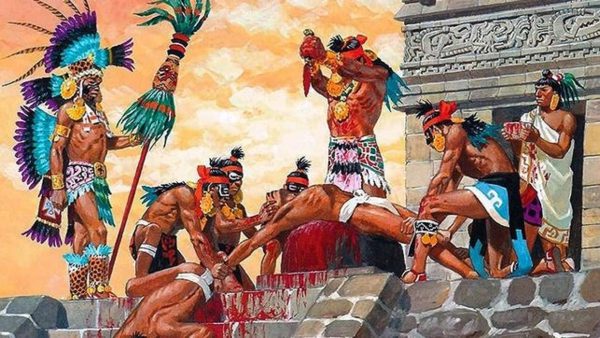

The role of Cacao in the sacrifices of the Mayan civilization

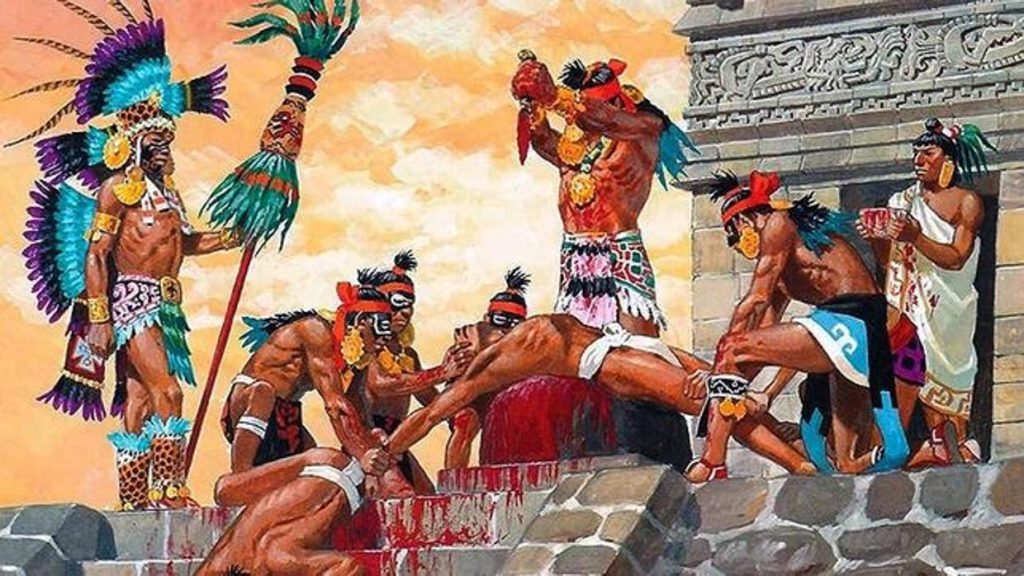

During rituals, cocoa could be mixed with psychoactive mushrooms, seeds and flowers.

According to Friar Durán (1967), when a representative of Quetzalcóatl was going to be sacrificed, if he became sad and did not want to dance, they gave him a cocoa to drink where knives had been washed with human blood from past sacrifices; He had no memory of what they had told him and returned to the dance.

In weddings between Mayan sovereigns, cocoa was an important part of the ritual, as shown in plate 26 of the Nuttall Codex, of Mixtec affiliation, in which the marriage of “Deer” with “Flower Serpent” is celebrated, who gives him a cocoa pot.

The Mayans held an annual festival in April to honor the cocoa god, EkChuah,

festivals that preceded the planting of cocoa. In this festival, dogs with cocoa-colored spots and blue iguanas were sacrificed. (Coe and Coe 1999, Furst 1977).