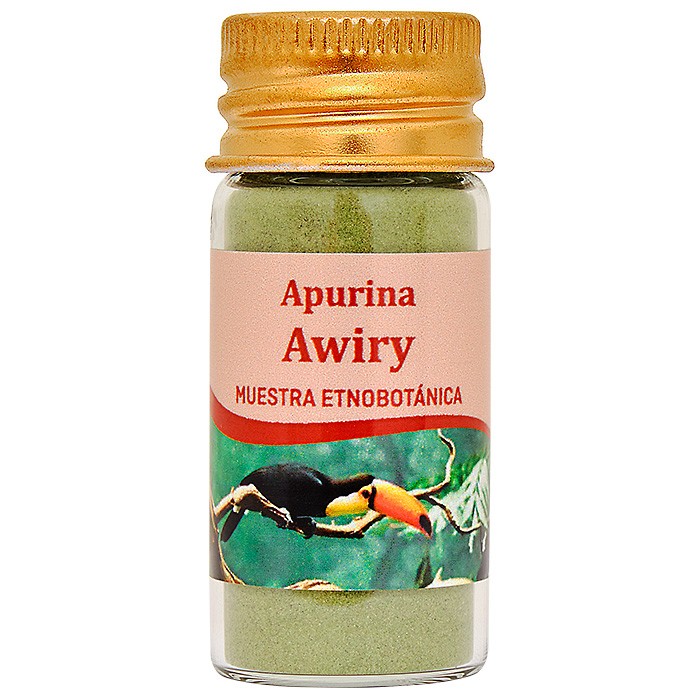

Apurina Awiri

28,00€

The Apurinã are famous for their green Rapé, unique and completely different from the other tribes in the region. It is made from a sacred plant called Awiry, considered by some to be a type of wild tobacco.

The Apurina Rapé does not contain ashes or tobacco; Only finely sifted and ground Awiri leaves that give it its characteristic green color, and is a perfect variety for those who want a nicotine-free rapé.

To make rapé with tobacco, the tobacco is fermented during drying and rolled up on sticks or ropes for storage. The Awiry, on the other hand, is not fermented or heated; it is simply left to dry, and then it is directly ground, so it maintains its green color and can be considered a raw and alive Rapé.

Among the Apurina, only a few communities cultivate awiry; most of the crop needs to be gathered. It grows on the banks of rivers and can only be harvested in the dry season, since when the river grows the area where this plant lives is flooded.

Therefore, this rapé is considered rare and special. While most indigenous Rapés are blown with a Kuripé or Tepi, the Apurinã Awiry is traditionally inhaled through a tube, similar to the use some of the tribes make with the Yopo.

-Intensity: Mild

-Proportion: 100% Awiry

-Tribe: Made by the Apurina tribe

-Composition: Ground and sifted Awiry leaves.

-Size: 10 ml bottles (8 to 9 grams).

-Use: Ethnobotanical curiosity.

Apurina Tribe

The Apurina live scattered in places near the banks of the Purus. They have a rich cosmological and ritual universe, despite the fact that their history has been greatly affected by violence at the time of rubber cultivation in the Amazon region.

Today they continue to fight for their rights; some of their lands have not yet been officially recognized, and are constantly invaded by loggers.

Some argue that Apurinã, or in its oldest form, Ipuriná, is a word from the Jamaica language. The group’s self-identification is popũkare. Some ancient texts refer to the word kãkite as the self-identifier. Kãkite means “people” but, according to some Apurinã, kãkites simply means “people” in the sense of the human species (“I saw people”, as well as “I saw monkeys” or “I saw jaguar”), rather than in the sense of an individual community or ethnic group.

The Apurinã language is a member of the Purus branch of the Maipure-Aruak family (Facundes, 1994). The closest related language is that of the Manchineri, or Pyro, who inhabit the upper Purus in Brazil and, in Peru, mainly the lower Urubamba valley. Some Apurinã argue that they can also understand a little of the Kaxarari language.

The Apurinã inhabit 27 indigenous lands, in different stages of the official recognition process; Twenty have been fully demarcated and registered, three have been declared for their exclusive use and four are in the identification study phase. The total area of these completely demarcated indigenous lands is 1,819,502 hectares; of these two are shared with the Paumari of Lake Paricá and the Paumari of Lake Marahã and one with the Torah, in the Indigenous Land of the same name.

The Apurinã of the Pauini region are divided into two clans: Xoaporuneru and Metumanetu. Membership in one of these groups is determined by paternal lineage. For each of the clans there are prohibitions on what one can and cannot eat. The correct marriage is between Xoaporuneru and Metumanetu, since marriage between members of the same clan has the same consideration as marriage between brothers. This is the term, furthermore, that two members of the same half can use when addressing each other (nutaru, brother, nutaro, sister), just as Xoaporuneru and Metumanetu are sometimes called nukero (sister-in-law) or nemunaparu (brother in right). The names of the people indicate which of the “nations” they belong to.

The Apurine Mystic

“Who is your God? I don’t know; I only know that his name is Tsora.”

Artur Brasil Apurinã, Mũpuraru, Artur the Shaman, thus speaks of Tsora or, in its translation: God. Tsora is the creator of everything on Earth and for this reason he is called God. The story of Tsora, the story of the beginning of the world, the beginning of everything, always begins in its many versions with Mayoroparo, or “after the earth caught fire.” Mayoru means vulture and Mayoroparo is a monstrous woman, a witch who devoured the bones of those who disobeyed and kept the bones of those who obeyed.

Tsora created people and the different types of people, the different peoples: Apurinã, whites, other Indians. He administered various tests to these peoples and the Apurinã always did worse than other Indians and whites. That is why, the narrators say, that despite being “the best there is,” the Apurinã are few and divided among themselves.

Another Apurinã legend is that of La Tierra Sagrada and the Otsamaneru tribe. The Apurinã were immortal and lived in a land where nothing got sick or died. They accompanied the Otsamaneru, traveling between one land of immortality and another. However, they were too enchanted by the things they found in the “mortal lands” that lie among the sacred lands, and ended up staying there.

The Kaxarari are frequently identified as the companions of the Apurinã on this journey. According to some accounts, the three peoples traveled together: Kaxarari, Apurinã and Otsamaneru. The Kaxarari were the first to be enchanted with the fruits of the “mortal lands”, and then the Apurinã; while the Otsamaneru continued their journey.

Apurina ritual celebrations

Ritual celebrations of the Apurinã, generically known as Xingané (in Apurinã, kenuru) range from small evening song sessions to larger-scale events that involve invitations to various villages and offer feasts, cassava wine, bananas, and palm fruit. patauá. Sometimes these are rituals to pacify the souls of the dead, immediately after their death or on anniversaries. In such cases, according to Abdias, the ritual is known as isaĩ.

A Xingané begins with a ritual confrontation. Guests arrive from the forest armed, painted, and decorated. They come screaming. The hosts, similarly armed, go to meet her. When they meet the leaders, they step forward and begin to argue, speaking quickly and loudly (this dialogue is called “cutting sanguiré” in Portuguese and katxipuruãta in Apurinã), all the time with their weapons pointed at each other’s chests . Behind are the other members of the group, ready, and with their weapons pointed similarly to those involved in the discussion. When the voices are lowered, so do the weapons, and the leaders proceed to take the tobacco from each other’s hands.

At the beginning of the discussion, each one declares that he does not know the other and asks who he is. Then follows the sanguiré, a personal speech that always closes with the confirmation of the speaker’s parents and grandparents. Camilo Manduca Apurinã sums it up like this:

“When you cut the sanguiré you have to remember the name of your father, mother, grandfather. What you want to say, you have to say at the moment of the sanguiré. Whatever is happening, you must find out during the sanguiré.”

Apurina Shamans

For the Apurina, the origins of the disease and the shaman’s cure are stones. A stone is what allows the shaman to heal and what allows him to cause disease and death. During the beginning of a shaman’s training, the first step is for him to stay for months in the forest, fasting or eating very little and chewing katsowaru. Sexual intercourse should also be avoided.

An Apurinã shaman works through dreams. In these, his spirit leaves, visits other places and performs tasks. Other spirits guide the shaman on these journeys: the animals and the heads of the animals (hãwite) with whom he works. Each shaman has one or more of his own: the jaguar, the snake or the mythical mapinguari.

What others see as animals, the shaman sees as people and some as family.

One of the functions of a shaman is, for example, to make them stop “tormenting” or to stop snakes from biting.

If they are strong, the shamans will travel to different lands: under the ground where they live, even under the river, even in the sky where Tsora lives. The stronger the shaman, the more places his spirit can go.

The Apurina and the rubber harvesting

Systematic contacts between the Apurinã and non-Indians began as a result of rubber gathering. The Purus valley began to be explored during the 18th century by itinerant traders in search of the so-called “drugs do sertão” (products of the interior): cocoa, copaiba balsam, turtle fat and rubber. Some of these explorers settled and processing plants began to be established in the lower Purus. In the 1850s and 1860s several expeditions were sent to explore and map the river. By this time some Apurinã were reportedly already working for non-Indians.

The Purus was occupied by rubber. Exploitation began in the 1870s and in 1880 the Purus was occupied by non-Indians in its entirety. Rubber harvesting declined after 1910 when Asian production began, against which Brazilian production could not compete. Without a market, the rubber estates were abandoned by the owners. The seringueiros (rubber pickers) and Indians continued to survive through subsistence agriculture (which had been largely prohibited on rubber farms) and the marketing of other products such as Brazil nuts.